Soemadi saw far in the sky horizon an amphibious Catalina plane approaching the swampy area just near Tulungagung, East Java. He got an order to pick up some VIPs coming from a faraway land with his brand new tires sedan. It was on the morning of August 10, 1948, when the plane landed and he saw at last two passengers got off the plane. He recognized the first, slim, and tall passenger as Soeripno, the Indonesian representative in Praha, but not the second one who just introduced himself as Soeparto, the Soeripno’s secretary.

The long journey to Solo didn’t make him close to this rather obscure secretary as though he just fell from somewhere in the sky after disappearing from his homeland for so many years. On their arrival in Solo, his curiosity arose when Wikana, the dismissed Military Governor, then one of the leaders of People’s Democratic Front (FDR), warmly welcomed them.

Soeparto alias Muso didn’t want to waste time. He started to campaign introducing his brand new concept, “the New Way.” He criticized PKI leaders for having no influential grassroots in laborers, farmers, youths, and soldiers. PKI cadres should act openly, he urged, not hiding behind People’s Democratic Front (FDR) as an underground party. Muso’s idea to establish a National Front was supported by Amir Sjarifuddin, saying that the “Oude Heer” would undoubtedly accelerate the program they had set up.

On August 13, Muso met Soekarno at the national palace, Jogjakarta, where the two old friends were warmly embracing each other. They had lived and spent their youth time together in Tjokroaminoto’s boarding house when they were in high school. At the end of the meeting, Soekarno called for Muso to appease the clash between political factions for which Muso answered pretentiously: “I do come here to establish order.” His words sounded somewhat puzzling, but nobody suspected that he would dare to stab Soekarno from behind.

On that very same day, within PKI’s political bureau, Muso just forgot his warm meeting with Soekarno a couple of hours before and criticizing the latter the way he led the Indonesian revolution. For him, Soekarno was a mere nationalist bourgeois who failed to revolutionize his government’s course of action.

Muso called for PKI to metamorphose into a radical party that should aggressively promote its ideology and launched armed struggles whenever necessary. On August 21, he took over the leadership of FDR and merged [illegal] PKI, Labor Party, Socialist Party, and Pesindo into a single party, the legalized and open PKI. He aimed to make the national army to become people’s army established from and for the people.

Some Labor Party leaders such as S.K. Trimurti and Asranudin refused to merge with PKI unless FDR held a plenary meeting to agree upon. Notwithstanding, Muso ordered the leaders to swear against the government policy, criticized Amir Sjarifuddin for having dissolved his cabinet, giving way for the rightists to take over the political power. In auto-criticism, Amir Sjarifuddin admitted for having received 25 thousand guilders from Van der Plas to establish underground movement against the Japanese.

In a show of force the next day, Muso demanded in front of 50,000 people the replacement of the current Soekarno-Hatta cabinet with that of the national front. On September 5, after declaring PKI as an open political party, he stated the importance of ratifying diplomatic relationships with the Soviet Union.

To introduce his revolutionary ideas, Muso held a safari tour to Solo, Madiun, Kediri, Jombang, Bojonegoro, Cepu, Purwodadi, and Wonosobo. He felt that the time was ripe for a proletarian revolution he longed for, for a long time. It was a long dream, a dream that he had since, together with Alimin, were imprisoned for having steered the revolt of Islamic Union (Serikat Islam) Afdeling-B in 1919.

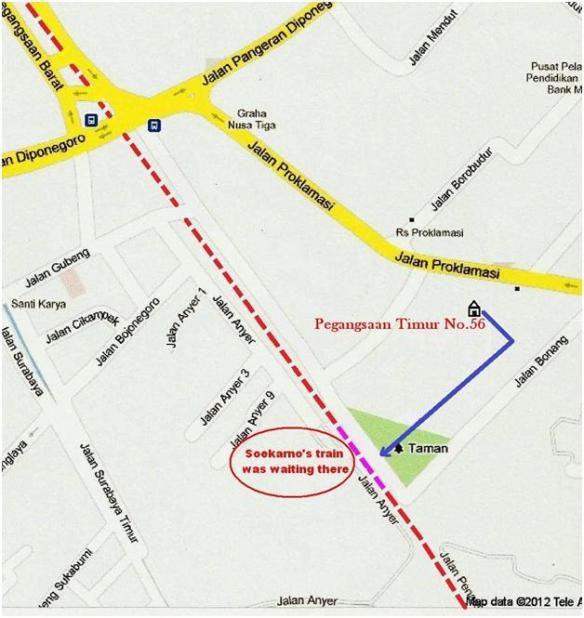

In his status as a PKI fugitive, in December 1925, he attended a secret meeting in Prambanan, Central Java, aiming to organize armed revolts against Dutch colonial within six months. However, before they executed the plot, Muso, together with Budisutjitro and Sugono, the head of the Train Labor Organization, had to escape to Singapore as the Dutch would capture them in early January 1926.

In Singapore, they joined with other PKI leaders: Alimin, Subakat, Sanusi, and Winata, continuing their plot against the Dutch administration as they previously planned. Musso sent Alimin to inform Tan Malaka in Manila, who had become the Komintern’s representative for Southeast Asia, about the Prambanan Plan. Upon the request for him to get Moscow’s support, Tan Malaka refused to do so. He considered the timing was too early and the Dutch administration would easily crush such a weak movement into pieces.

Alimin returned to Singapore and, together with Muso, decided to go to Moscow without Tan Malaka acquaintance. Being unaware of their departure, Tan Malaka sent a report to Komintern in Moscow about the Prambanan Plan, which made Stalin very upset and demanded an immediate abortion of such blunder decision.

But it was too late. Muso and Alimin were on the way to Moscow, while Tan Malaka’s effort to convince his colleagues to abort the plot was with no avail. On November 12, supported only by few branches from Batavia, Banten, Priangan, and West Sumatra, revolts broke through. The Dutch government quickly crushed them and hanged three of the revolt leaders. They declared that PKI was illegal, arresting a total of 13,000, around 9,500 were in jail, and 1,300 were in a remote area in Digul, Papua.

Having learned that the Communist revolt in his country failed, Muso decided to stay in Moscow, joining the Soviet Communist party in which he got the position as the Indonesian affairs section. Under the disguised name of Krause, he used the Communist international media to attack Tan Malaka, qualifying him as Trotskyist, a traitor who deserved to die.

Stalin aggressively attacked Sun Yat-Sen and Mahatma Gandhi as nationalist bourgeois in Komintern Congress, July 1928, but said nothing about the Communist leaders in Indonesia. It was a gesture of Stalin for Muso to continue his revolutionary movement, albeit he was responsible for the blunder. Muso took this blessing to blame the conflicting PKI leaders for their wrong steps in doing the revolts in Java and Sumatra. Soon after the Congress, Muso had been given the honor as Komintern executive committee member.

In April 1935, Siti Larang, the wife of Sosrokardono, the founder of Sarikat Islam (S.I.) Afdeling-B, then a member of the progressive women movement in Surabaya, met an obscure guest in Simpang Hotel as instructed by Pamudji, the chief of Indonesia Berdjoeang newspaper. The guest was nobody but Muso, who just appeared from his long exile abroad asking for a rented house for him to stay. He took advantage of Dimitrov doctrine, a Komintern strategic change, to rebuild PKI. The principle instructed Komintern members elsewhere to cooperate with their colonial governments to hinder the aggressive fascist movement worldwide.

In several cities, Muso established Democratic Front of Antifascist, also called as the young PKI or PKI 1935 led by seven members of Comintern congress. One of them was Pamudji, the chief editor of Indonesia Berdjuang newspaper, later appointed as one of PKI Central Committee leaders. Muso didn’t miss the opportunity to publish Dimitrov doctrine in Pamudji’s journal intensively.

Muso recruited Sudisman and Soemarsono, and many other young PKI cadres in Surabaya and Solo, influenced Amir Sjarifuddin joining PKI through the leftist Perhimpunan Indonesia. However, the Dutch were not impressed with such doctrine, and their intelligence, Politieke Inlichtingen Dienst, arrested and exiled many of them to Digul mixing with the previous 1926 PKI dissenters. Pamudji managed to escape from the detention, and Muso secretly slipped away back to the Soviet Union.

PKI partisans, however, continued their underground activities, and many of them secretly diffused to the colonial government administration as well as political organizations such as Gerindo and Socialist Party. Amir Sjarifuddin was one of the prominent activists who deliberately cooperated with the Dutch. Later he acknowledged that he received money from Van der Plas to establish underground movements before the Japanese entry.

His underground activities against Japanese occupation made him together with Pamudji, and hundreds of others were sentenced to death in 1944. He alone was saved by the bell thanks to Soekarno-Hatta for their interference asking for amnesty.

Amir Sjarifuddin kept following the Dimitrov Doctrine until 1948 when he ratified the Renville Agreement. This agreement raised the eyebrows of Moscow leaders as it was against Zhdanov Doctrine they had adopted since September 1947, a strategy that ended the cooperation with the nationalists and colonialists elsewhere

Having lacked information, Muso defended Amir’s action, which he considered as merely a tactical movement. He further guaranteed that the leftist influences in the Republican military became stronger. Alas, within days, Muso’s arguments were crumbled. Amir resigned from the Prime Ministry position and, Masyumi and Indonesian Nationalist Party, the Communist rivals, were getting stronger. This event caused Moscow’s harsh criticism toward Muso.

Russian analysts accused Muso as daydreaming justifying a strategy that led to calamity. Muso took his time to contemplate the criticism before making the responsibility to the central role to rectify the party struggle and ready to come back to his country for taking over the Communist leadership.

Following the dissolution of Amir cabinet, Sjahrir quitted the Socialist Party and established the Indonesian Socialist Party (PSI). Having his agenda, Amir merged Socialist Party into People’s Democratic Front (FDR), which he set in Solo on February 26, 1948. On top of his Socialist Party, others joined FDR, such as [illegal] PKI, Labor Party, Pesindo. As the FDR chairman, Amir took the side with Soviet instead of American capitalism and openly declared his desire to topple down Hatta, through rebellion if necessary.

In early April 1948, being depressed from Moscow criticism, Muso went to Praha to meet Soeripno, Indonesian representative posted there since 1947. Muso disguised himself as the secretary of Soeripno. Under the influence of Muso, Suripno opened a diplomatic relationship with the Soviet Union. This action made Hatta furious and called him back in less than a week to Jogjakarta.

Muso followed suit, taking a long journey from Praha-Cairo-New Delhi-Bangkok-Bukittinggi, kept hiding his own identity. Any time he was photographed, he hid his face behind a book or newspaper. As they landed at last at the swampy area near Tulungagung, Soemadi could see the optimism and courage radiated from Muso, then disguised as Soeparto, who was ready at all cost to make his dream come true, the establishment of Indonesian Soviet government.

Within half an hour, the Dutch red beret troops took over the airfield without even having a casualty. The Republican lost 33 lives, mostly academy cadets, four warplanes under repaired, and Avro Anson small passenger plane ready to take off. They soon established n airlift Semarang-Maguwo transporting around 2,600 troops of Regiment Stoot-troepen, 80 battle jeeps, a significant amount of ammunition, and logistics enough for three days battle.

Within half an hour, the Dutch red beret troops took over the airfield without even having a casualty. The Republican lost 33 lives, mostly academy cadets, four warplanes under repaired, and Avro Anson small passenger plane ready to take off. They soon established n airlift Semarang-Maguwo transporting around 2,600 troops of Regiment Stoot-troepen, 80 battle jeeps, a significant amount of ammunition, and logistics enough for three days battle.