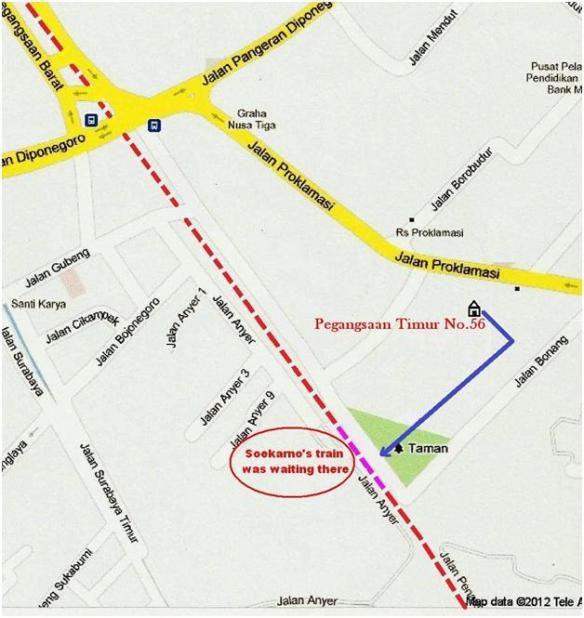

On the quiet evening of January 4, 1946, a series of railway carriages silently halted behind Soekarno’s East Pegangsaan residence, situated beside a railway track. Without causing any disturbance, Soekarno, Hatta, their families, and staff slipped into an unlit carriage unconnected to the others. A loyal train operator waited in the locomotive cabin, keeping a safe distance from the carriages.

This sight was not unusual, as a solitary carriage waiting to join others was a common occurrence. Upon a signal, the locomotive approached and coupled the carriage with the rest. Under the cover of a moonless night, Soekarno and his companions clandestinely embarked on a journey eastward to Jogjakarta, the forthcoming capital of the Republic.

The decision to depart was made the previous night due to the deteriorating situation in Jakarta. “The situation in Jakarta has become untenable. Tomorrow night, we will relocate the capital to Jogjakarta. No one should bring their belongings,” Soekarno warned. “There’s no time to pack everything, furniture or otherwise. You will stay close to me at all times for your safety.”

Following the landing of Allied soldiers in Jakarta and various parts of Java in September 1945, tensions escalated. By September 15, British First Admiral Patterson arrived at Tanjung Priok harbor aboard the HMS Cumberland, accompanied by Charles Van der Plas, the representative of the Netherlands Indies Civil Administration (NICA) at the Allied headquarters in Singapore.

After a minor incident with young Republicans, Van der Plas suggested to his British counterparts that eliminating the Japanese-created Republic would be swift and straightforward. Lowering the “red and white” flag from government buildings, capturing Soekarno and other leaders as Japanese collaborators and war criminals, would erase the Republic from history.

The situation for the Republic worsened when Hubertus J. van Mook, the Lieutenant Governor-General of the Netherlands Indies, returned to Jakarta on October 5 from Brisbane, Australia, the headquarters of the Netherlands Indies government-in-exile. NICA soldiers, bolstered by ex-Japanese detainee Dutch soldiers, intensified their reign of terror in Jakarta, shooting anyone deemed suspicious.

In response, Soekarno imposed a curfew, but Dutch patrols continued to wreak havoc, looting homes, and terrorizing families. Clashes between the Dutch army and Jakarta residents escalated, with NICA soldiers committing atrocities such as abducting youths and shooting civilians without cause.

There were numerous attempts to capture or assassinate Soekarno. Once, during a late-night meeting with his ministers, Soekarno’s driver went to buy food only to have their vehicle collided with a military truck. The soldiers, believing Soekarno was inside, narrowly missed a fatal crash.

Due to the constant threat, Soekarno and his entourage had to constantly change their sleeping locations, avoiding open spaces or roads. Remaining in Jakarta was no longer an option; it endangered not only his life but the survival of the nation.

To counter foreign accusations of collaboration with the Japanese, Soekarno appointed Sjahrir as prime minister on November 14, 1945. However, this move drew criticism domestically for being unconstitutional.

With Indonesian armed forces withdrawn from the capital and no reliable police units deployed, the NICA army in Jakarta operated unchecked. On January 3, 1946, Soekarno decided to relocate the capital to Jogjakarta to escape the Dutch threat.

The “ghost train” carrying its notable passengers finally arrived at Jogjakarta, the new capital of the Republic of Indonesia. Although the exhausting journey ended, it marked the beginning of a new chapter. Indonesians now faced critical decisions: diplomacy or military action, survival, or demise, freedom, or death.